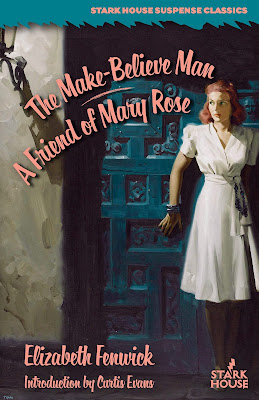

Like Fenwick's A Friend of Mary Rose (1961), which traps the reader and characters in an attic to contend with a home-invasion plot, or The Make-Believe Man (1963), which confines the compact narrative into a different type of home-invasion suburbia, Disturbance on Berry Hill (1968) has a similar set-up.

In Fenwick's taut narrative, which she had perfected by this point in her career, the thrilling mystery lies in a small cluster of upscale homes on Berry Hill, a sub-division that was carved out of a sprawling farm in rural Connecticut. These seven homes are mostly owned by affluent, middle-aged couples that fit the mid 20th century mold – husbands journey off to daytime employers and wives remain behind to keep the home fires well lit. But, on Berry Hill someone else is staying behind as well, stalking and menacing these prosperous homes and providing white-knuckle fright for the ladies.

The novel begins with Maggie Leavis recounting a frightening incident that occurred while she was in the bathtub. From inside the porcelain safety, Maggie hears someone enter the home, walk upstairs, and then methodically stand outside of the couple's bathroom – knowing Maggie is inside. Before you think Michael Myers, Maggie explains that this intruder, who she thinks was a mysterious man, didn't come in the bathroom and instead simply knocked a picture off the dresser and then slowly left the home. The author introduces readers to Berry Hill in a really significant way. Maggie's testimony is bone-chilling.

When Maggie visits her female neighbors the next day she hears similar stories. In one account, this mysterious man closed a garage door behind a woman and then stood outside as if he (or it!) was daring the woman to open the door. In another incident, a woman is grabbed from behind and squeezed. The attacker then simply runs off. There are a few similar things, like a birthday cake flipped upside down or seeing someone near the creek behind the neighborhood.

The neighbors all meet one night to discuss the intruder/prowler and what needs to happen next. Should they call the police? Ignore the rather innocent pranks? After the meeting, their concerns are met with an appalling revelation – one of the female neighbors is found dead near the creek. When the police arrive they discover it was foul play. Whoever has been gently plaguing Berry Hill has now escalated their game into cold-blooded murder.

Disturbance on Berry Hill is the proverbial page-turner. Fenwick's approach to the book's first half sets readers on edge with these disturbing intrusions into the sanctity and lives of these well-to-do Connecticut residents. As their white-collar emotional fencing caves, the flaws and vulnerability begin to show. One elderly neighbor is contending with dependency while another couple is dealing with depression and inadequacy. There are also the obvious early dismissals of the complaints by most of the men, who are either too busy to deal with the intrusions or simply believe these are daytime fantasies created by bored housewives.

Fenwick knows when to increase the pace, tension, and atmosphere for the book's second half. After the murder, fingers begin pointing, accusations are made, and there is a real unnerving, unraveling of the neighborly ties that bind. Someone in the neighborhood is, or knows, the murderer. Through Maggie's experience, the readers delve into the mystery and eventually discover the identity of the killer.

While the ending left me slightly deflated, Disturbance on Berry Hill was an extremely enjoyable read. The characters, the setting, and the slow atmospheric march to the murder really highlighted the book's opening half. As the book sped to the finish, fans of police procedural crime-fiction will enjoy the investigation and interviews.

Overall, Fenwick continues to impress. If you are wanting to explore her work look no further than Stark House Press's amazing preservation. They continue to focus on Fenwick, and her contemporaries in Jean Potts, Ruth Sawtell Wallis, and Nedra Tyre to name a few (I'm pushing on them to reprint Amber Dean!). You can get Disturbance on Berry Hill as a twofer with her 1961 thriller Night Run HERE.