I decided to try another literary work from Bruce Elliott, so I thumbed through some online pulp magazines and found a novella titled “Do You Know Me?”. It was published in the rather tame Thrilling Detective publication, specifically the February 1953 issue. This story follows an entertaining but average Shell Scott story (“Murder's Strip Tease”) by Richard S. Prather. That's not criticizing Prather's work, but I say that just as a stark comparison to what Elliott contributes to this issue. In Prather's contribution, a client wants to pay Scott to get a blackmailer off of his back. In Elliott's story, a deranged psychopath is preying on New York City by slicing off faces to destroy “masks”. Needless to say, Elliott was pushing the envelope, especially when you examine the full scope of what he's offering to his readers in this 24-page story.

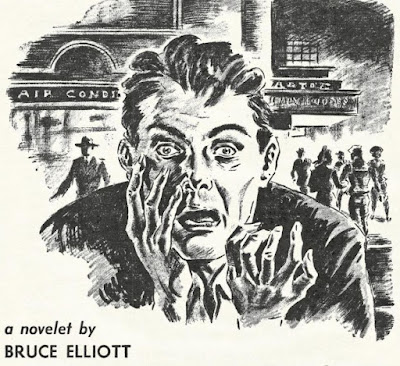

The story is set in New York City over the course of a crisp autumn day. The author introduces “the man nobody knew” as a resident of a West Forty-Seventh Street apartment just east of Broadway. The room in which the man awakens has door frames and windows stuffed with newspapers. The radiator weazes its first harsh clanking of the season and the stove's greasy burners permeates the air with a rank smell. Beside the bed, written in lipstick, an ominous message is scrawled: Since you can't catch me, and since I don't want to kill again, I'm going to kill myself.

The unknown man, who I'll simply refer to as “the killer”, is described as experiencing torturous thoughts as his days and nights are filled with agony. Elliott states “the plastic shell that surrounded him was slowly dissolving." This isn't the only time that the author describes this killer as if he is a mannequin, some sort of killer that awakens from a stiff catatonia once the plastic dissolves. He even goes as far as saying the killer's movement was like “a deep sea diver inside his suit”. This covering – metaphorically – is detailed as a gelatinous mass that surrounds bone and tissue. Like some macabre Hemingway fault, this character is stricken with some sort of physical ailment that contributes to his psychological trauma. The killer is terrifying, made more so by the six-inch razor-sharp blade he keeps in his jacket pocket.The killer emerges into the night and approaches a prostitute. He asks her repeatedly, “do you know me, do you recognize me, and where do you know me from?” The prostitute doesn't know him, and fakes interest to lure the killer upstairs. In hopes of turning a trick for money, she quickly realizes that the killer was very serious with his questioning. When he discovers she doesn't know him, he kills her. In his mind, he asks himself why he can't cut and rip off the “mask” while the victims are still breathing. This is really savage stuff for Thrilling Detective, but Elliott ups the ante.

A wealthy advertising agent named Thomas is introduced. Thomas lives in the suburbs of Mount Vernon and travels to the city each day for work. Three days a week he attends therapy sessions because Thomas doesn't want to be a man. He despises his wife and is ashamed of his young son because the child's existence proves that Thomas is in fact a biological man. After leaving his therapy session on Park Avenue, Thomas decides that this night he is going to forget women and throw away his whole miserable life. Elliott describes Thomas' agenda: “Tonight he wanted a man and he didn't care if it was dangerous, and he didn't care if rough trade sometimes turned on you and beat you up, and sometimes even killed you. He wanted a real man.” Needless to say, this is provocative stuff for a mainstream pulp in 1953.

Through the course of Elliott's compelling, awe-inspiring story, more characters are introduced, each with their own backstory. What the author is presenting is a cross-examination of the diversity of New York City. A young waitress is introduced, along with her boyfriend, a city police officer, a doctor, and two Russian-born immigrants. All of these characters entwine in a disturbing series of events that mirrors an active-shooter situation today. In this story, the killer begins randomly murdering people in nightmarish fashion in the middle of Times Square.

Elliott's provides some riveting stuff involving sexuality, social unrest, and mental illness. Circling back to the opening statements of this review, Elliott's One is a Lonely Number could have never been published in today's market. However, this author's short-story certainly could have been published today, but seems unfitting and way ahead of its time for 1953. It’s a reversal. I question how “Do You Know Me?” could have possibly been published in that conservative era. It is art imitating life, as if Elliott himself is asking the question of his readers and publisher. Even when you look at the more violent publishing turn with 1947's mature I, the Jury, written by Mickey Spillane, the mainstream literary world wasn't exploring sexuality and mental trauma in such an obvious way. Elliott's writing is just so abstract and impressive here. The message is subjective and in the eye of the beholder. I strongly encourage you to read the story for free online (linked below), or track down the expensive back-issue.